Welcome back! Below is a quick summary of what we discussed, with time stamps, followed by a complete transcript below the line.

00:41 — What Michael has experienced living in Beijing during the transition from “Zero Covid” to “let it rip”.

09:51 — How the surge in commodity prices has affected Europe, Japan, and the major energy exporters other than Russia

29:54 — What the war has meant for Russia

34:06 — What the rest of the world can learn from Russia’s experience, and why Germans and Japanese might regret saving for retirement by investing mostly in other rich countries

Matthew Klein: Hello and welcome back to UN/BALANCED, a listener-supported podcast about the global economy and a financial system. I’m Matt Klein.

Michael Pettis: And I’m Michael Pettis. Today we’re going to discuss how the ideas we laid out in Trade Wars Are Class Wars, which is the book that Matt and I published a couple of years ago, help make sense of the economic and financial consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which of course is one of the big stories of the last year.

Matthew Klein: And we’re really looking forward to getting into that. But first, what I really would love to talk with you, Michael, about is all the things that you’ve been experiencing and seeing living in Beijing over the past few months with China’s transition from “Zero Covid” to essentially a herd immunity strategy. I’d love to get your sense of what that’s been like, being on the ground.

Michael Pettis: It’s what we continue talking about almost all the time here in Beijing. Now one of the things that shows how quickly things are changing in China—and in the biggest cities more specifically—is I had a meeting at my house earlier today with some people from the Israeli embassy. [We recorded on January 12.] The meeting was scheduled at 4:00. And by 4:20 they were sending me frantic messages saying, “We’re stuck in traffic, we’re going to be late, we’re stuck in traffic, we’re going to be late.”

And I thought that was pretty funny because, you know, traffic in Beijing has been really horrible. Beijing is famous for the terrible traffic. But in the last two, three years, we completely forgot about that. Because of the “Zero Covid” policy, nobody ever went out and you could travel from one side of town to the other side of town in half an hour. And now as we’re returning to normalcy, we’re all remembering how bad the traffic is.

It’s no longer possible to drive quickly across town. It takes an hour or an hour and a half. That's a story about how quickly things are reverting to normal here in places like Beijing, Shanghai, and a few others of the what they call the “first tier” cities.

It feels like we've gone through most of the Covid wave. I’ve been trying to think about how many of my friends here haven’t caught Covid, and I can only think of one person who’s told me he still hasn’t caught it yet. Everybody else has caught it. And so I would say almost everybody in the first tier cities has gone through that first wave of covid. So in a couple of weeks it will be behind us.

But not necessarily for China, because in the second- and third-tier cities and in the rural areas, they haven’t really caught the wave. But this year, Chinese New Year comes very early, so everybody is going home for the New Year to be with the family. What everyone’s pretty much expecting is that the next really big wave of Covid will hit the smaller cities, the towns, and the rural areas, and we’ll get a huge spread of Covid there. That’s going to be much more problematic because those areas simply don’t have the medical facilities that we have in Beijing, Shanghai, et cetera.

The bad news is that the death rates are pretty high. I heard this really astonishing statistic in the Chinese Academy of Arts and Sciences, which is, you know, you get elected to once you’re very prominent and probably older.

Typically, in an average year, they lose through death about 16 members. In the last month, 20 members have died, which gives you an idea of the impact Covid is having on a very unprepared population.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that it’s happening so quickly that probably by the end of February, beginning of March, most of China will have gone through the big covid wave, and so we'll start to see a real opening of the economy fairly soon—I think much earlier than people expect. So that’s the good news.

And then a story that you might find funny. It shows you how entrepreneurial people in China can be. There are various variants of covid that are sweeping through Beijing, and they seem to have very different impacts. The variant that I had was really minor, basically for about a week I was too tired to do much work. Otherwise, I was okay. But other variants have been really, really painful. People have been out of commission for more than two weeks with a horrible sore throat so bad that they can barely drink.

So about two or three weeks ago, we started to see on Weibo, which is the Chinese Twitter, that people were advertising that they had the better variant, the less painful variant. And for a fee they could come to your house so that you would be guaranteed the better variant and you would be protected from the worse variant. I don’t know how many people took advantage of that, but it just goes to show how quickly people have adapted to the new conditions. So I think we’re going to continue to see that.

Matthew Klein: That’s a fascinating story. Well, I certainly hope everyone is able to get through it as safely as possible.

I know one thing you wrote about recently, which I thought was striking, was the extent to which a lot of people within China were not fully prepared for Covid being quite as virulent as it would be when they did the sudden switch in policy. Is there a debate now among people within China about how things could have been done differently? Or is that just not how people approach this question?

Michael Pettis: There is a very big debate, not very public, because it’s very hard to have this debate without asking some potentially embarrassing questions. But what’s surprised many people is the way we went within one or two weeks from “Absolutely no way we’re ever going to open up, ‘Zero Covid’ has been incredibly successful and it will continue to be incredibly successful” to “Covid is not a problem, go ahead and catch it, it doesn’t really matter.” And a complete openness.

Now, we all knew at some point that this was going to happen, right? I spoke to people like you and other friends in the U.S. and Europe, and what you guys made very clear to me is that these new variants are spreading so quickly that there’s simply no way you can prevent it from spreading in a country like China. And people have known this for quite a while.

For example, I used to get my Covid tests over at my hospital because this would give me a chance to talk to doctors and nurses that I knew.

And I can tell you every doctor and every nurse, by March or April, they knew that at some point they were going to have to abandon the “Zero Covid” policy.

And I would say by the early summer—

Matthew Klein: Sorry, this was last March?

Michael Pettis: Yes. Last March or April.

Matthew Klein: Wow. Okay.

Michael Pettis: By the early summer, everyone in Beijing knew. It was just very clear that there was no way to stop the spread of Covid. So you would’ve imagined that if you know that, you know at some point you’re going to have to abandon “Zero Covid”, then obviously you should prepare for that point. And you should choose the best time to abandon “Zero Covid”, which most of us would argue would probably be in August and September of last year or March or April of this year. Don’t abandon it in the middle of the winter.

And yet, that’s exactly what they did. And they were completely unprepared for it, not just in terms of medicine. There was a black market for anything Covid-related—incredibly high prices because there was shortage of everything. Even things like ibuprofen, you couldn’t get, it was impossible to get except at incredibly high prices.

But other things too. So for example, in the first wave, nobody went out because they were so terrified of Covid. After three years of being told that “Covid is a disaster and we’ve protected you from it,” many Chinese not surprisingly believed that getting Covid would be a terrible, terrible thing. And so one of the things that happened is people stopped going out and donating blood. So blood supplies in the hospitals in China pretty much collapsed. The country was totally unprepared for it.

And so you ask yourself, the big question that people are asking, and you know they’re not answering it in public, is: how is it possible that China was so unprepared when they abandoned “Zero Covid”? Didn’t they know they were going to abandon it? After all, everybody knew that they had to do so.

So there are all sorts of questions about information flows—whether people at the top level of government are getting the same information that the rest of us are getting—because they really seemed unprepared for the incredibly rapid shift. They went from “Zero Covid is absolutely the right policy and don’t you dare take a step against that” to within a week or two, total openness. “Do whatever you want. You don’t need to test. We’re ending all quarantine. And don’t worry, it’s not a problem.” It’s a big surprise. There are all kinds of debates as to what really went on.

Matthew Klein: I’m still really struck by that point you made about how people back in March and April, which is when Shanghai was in the midst of its lockdown, were saying that “Zero Covid” was unsustainable, even then.

Moving on to lighter fare: war and death and famine and all that.

We mentioned at the beginning that the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and all the consequences of that for the world economy, are things that we obviously didn’t talk about in our book. Yet nevertheless, the framework that we laid out in our book and the examples we discussed are very helpful for thinking through some of the major consequences in how to analyze the situation. They’ve been very helpful for me personally, I think for you as well, and a lot of people who are trying to understand what's going on.

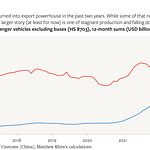

I think one of the most obvious points, and this is something we sort of hinted at the end of our previous episode, is that the large increase in commodity prices—because both Ukraine and Russia are such huge commodity producers in the war and that has disrupted a lot of the production and flow of these commodities to the rest of the world—has had some big implications for global imbalances in particular, among some of the major surplus countries pre-war, namely Europe and Japan and Korea. Although interestingly not China.

But in those others, the surpluses have really contracted. At the same time, we’ve had huge surpluses in some of the big energy producers, Norway, the Gulf, and Russia. Uh, you know, maybe you can lay out for us, sort of, you, you were saying that people in, you know, that policy makers in, in the places where the surplus have contracted in Korea and Japan and in Europe are now quite concerned about all this.

Maybe you can kind of lay out more about what they’ve been telling you and how you’re seeing this.

Michael Pettis: I was speaking to some officials from the South Korean Ministry of Finance, and they were very concerned about that because the current account surplus has disappeared. I think it’s even gone into a small deficit, and they thought that this was a terrible thing for South Korea and represented a major negative change going forward. I’ve read that in Japan they’re having a very similar debate. In Germany they’re having a very similar debate.

I try to think my way through “what does it mean for the current account to go from a big surplus to zero or a small deficit because of a rise in commodity prices?” And whether this is something that we have to, or they have to worry about forever. Well, the first thing, and, and maybe we’ll have a chance to discuss it later in this podcast, is whether losing your current account surplus is indeed a bad thing. I would argue that it isn’t. But nonetheless, there are many people who believe that growth is synonymous with running a current account surplus.

So the question then is: why would a rise in commodity prices cause the current account surplus to contract? And many people might say, “that’s sort of a dumb question.” If you’re a commodity importer, then the rise in commodity prices means that your imports are going up. And if your exports don’t go up, then by definition your current account surplus should contract. But of course, that’s not really, certainly in my opinion, I’d say in our opinion, because we’re very clear about this in the book, that’s not really the right way to think about trade surpluses.

You can’t really think incrementally. You can’t say, “assume nothing changes except commodity import prices go up, therefore the current account or the trade surplus will contract” because that assumption that nothing else happens is completely wrong.

Changes in your export revenues are redistributed domestically and the way they’re redistributed will then end up affecting such things as consumption and savings.

So that’s a long way of saying that I prefer to think about the current account surplus as the excess of savings over investment. That’s the definition—one of the definitions—of a current account surplus. So when a country’s current account surplus contracts, by definition, something must have happened in that country, because the external account must be perfectly accommodated by changes in the internal account, right? The two of them have to balance.

So when your current account surplus contracts—by definition—either your savings declined or your investment went up. Because the gap between the two must simultaneously contract.

So when I think about a country like South Korea or Japan or Germany or any of the persistent trade surplus countries, the question then is if you see a significant rise in commodity prices in your commodity imports then how does that affect your savings-investment imbalance? Well, it’s very unlikely that surging energy prices would cause you to increase investment. On the contrary, you might expect a slowdown in the economy—

Matthew Klein: Maybe it should, but yeah, you’re right. That’s not usually the impact.

Michael Pettis: It should, if the government decides to increase investment to match the rise in commodity prices. And there are reasons they may do so, but it’s very hard to do it quickly. So it’s unlikely that South Korean investment rose. So what’s much more likely is that there was a reduction in South Korean savings, right?

So why would a rise in commodity prices cause savings to go down? And I would argue the most likely way, and it’s probably the way it happened in all of these countries, is that importers—manufacturers, because they have to pay much higher commodity prices—that squeezed their profits. And remember that business profits are part of the savings. Businesses save all of their profits. So if you see a squeeze in the profits of businesses, then you’re basically seeing also a reduction in overall savings.

Now, how sustainable is that?

Well, the first way businesses tend to react to a significant increase in their input prices is with a significant reduction in profitability—until they’re able to raise prices by enough to pass the higher input prices over to their customers. So if you believe that the commodity price increases are permanent, then over time you have to raise the price at which you sell goods. And as you raise the prices, you basically pass on the increase in commodity prices over to your customers who ultimately are the consumers, right.

So what I would argue is that a rise in commodity prices represents a temporary decline in the current account surplus until either commodity prices go back down again or until businesses are able to pass on the increase to their clients, to their customers. What that tells me is that the contraction in the current account surplus is only temporary. For there to be a permanent reduction, you would really need a significant redistribution of income within South Korea, and that hasn’t really happened.

Matthew Klein: Two other quick points to add here, which are I think are relevant and interesting. In I believe all these countries, certainly in Germany and Japan, I don’t know as much about the Korean situation, the governments have laid out very expansive proposals—they actually implemented proposals to subsidize prices both for business and consumer customers for energy. And so essentially the other mechanism by which savings are being reduced is that the government budget deficits are increasing rather dramatically in these countries.

That’s probably the healthiest response here, in the sense that you have, of all the financial entities within the country, the one that is most able to absorb the extra debt temporarily is doing that in order to prevent people from having very extreme short-term declines in living standards.

But that’s also, and to your point, unless commodity prices remain very high—if they do remain very high, the government support is probably going to be withdrawn because of the view that consumers need to adjust—or commodity prices won’t remain high, in which case that government support is going to be pulled back.

The other component, which I’m not sure how much this applies in the case of Germany, but it certainly applies in the case of Japan, which is very interesting, is that while the trade balance has been blowing out due to high commodity prices, there’s been an almost commensurate increase in the income surplus. All of the dividends and interest and so forth on Japanese foreign investments has been rising very dramatically relative to the bills that Japanese are paying to the rest of the world. So that has been moderating the impact of the higher commodity prices.

And in fact, to the extent that central banks in the rest of the world continue to tighten the monetary policy in response to high commodity prices, they’re sort of naturally hedged a little bit on their balance of payments.

I think they may be unique in that respect, but it’s an interesting dynamic. It may also to a certain extent apply to Korea, but it’s an interesting dynamic there.

Michael Pettis: It probably applies less to South Korea, although as a surplus country, we know that South Koreans have accumulated, accumulated a lot of assets abroad. But it is something that I think that probably all of the countries that have run persistent surpluses should, in theory, be experiencing. Because if you own more U.S. assets and U.S. interest rates go up, your return on foreign assets should also go up along with that.

But I think really the key point is something that we talk about in our book quite a lot: the reasons for persistence surpluses have to do with the distribution of domestic income. And that’s why I would argue that if there’s been no real change in the ability of workers and households to demand a higher share of what they produce, then the change in the current account surplus or in the trade surplus is only likely to be temporary. Because at the end of the day, what matters is not whether commodity prices go up or down, but what matters is the distribution of domestic income.

Matthew Klein: So this presents an interesting question about the other side, which is the surpluses that have increased dramatically, particularly among the energy producers like Norway and the Gulf. Those presumably are also just as temporary. How are you thinking of that and the corresponding financial outflows?

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to UN/BALANCED to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.